- Homepage

- Conflict

- Format

- Albumen (3)

- Ambrotype (32)

- Cabinet Card (67)

- Cdv (5)

- Crayon Portrait (2)

- Daguerreotype (27)

- Hardcover (14)

- Multi-formats (6)

- Negative Photo Image (4)

- Photograph (6)

- Ruby Ambrotype (3)

- Sixth Plate (2)

- Small (2)

- Stereoview (3)

- Tin Type (8)

- Tin Type Photo (2)

- Tintype (160)

- Tintype Photograph (6)

- Unknown (9)

- ... (6675)

- Photo Type

- Album (10)

- Albumen (14)

- Ambrotype (199)

- Cabinet Photo (67)

- Cdv (480)

- Cdv & Tintype (6)

- Cdvs & Tintypes (7)

- Daguerreotype (84)

- Gelatin Silver (13)

- Mixed (3)

- Negative (10)

- Negative Photo (4)

- Opalotype (4)

- Other (4)

- Photograph (4)

- Snapshot (3)

- Stereoview (23)

- Tintype (527)

- Tintypes (3)

- Unknown (12)

- ... (5559)

- Subject

- Children & Infants (21)

- Civil War (31)

- Civil War Soldier (12)

- Ethnic (17)

- Family (24)

- Fashion & Costumes (10)

- Figures & Portraits (149)

- Genealogy (10)

- Historic & Vintage (90)

- History (24)

- Men (59)

- Men, Civil War (56)

- Men, Military (39)

- Military (98)

- Military & Political (579)

- Military & War (14)

- Portrait (15)

- Portraits (14)

- Soldier (12)

- Women (19)

- ... (5743)

- Type

- Belt Buckle (3)

- Carte De Visite (2)

- Cdv (3)

- Cdv Photograph (15)

- Daguerreotype (3)

- Full Cdv Photo Album (2)

- Illustrated Book (3)

- Negative Film Photo (4)

- Pendant (3)

- Photo Album (3)

- Photo Frame (2)

- Photograph (1359)

- Photograph Album (50)

- Picture Book (8)

- Picture Frames (8)

- Print (3)

- Real Photo (rppc) (10)

- Tintype (9)

- Tintype Photo (4)

- ... (5542)

- Unit Of Sale

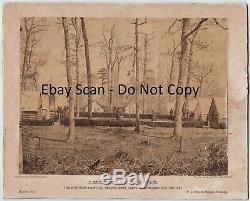

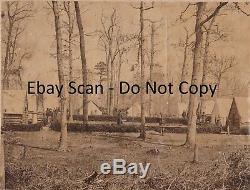

RARE Orig Albumen Photo Timothy H O'Sullivan 1864 Civil War Hospital Gardner

RARE Original Mounted Albumen Photograph. By Famous Civil War Photographer. Third Division Hospital, Second Army Corps, Near Brandy Station, Va.

For offer, a rare original photograph! Fresh from a prominent estate in Upstate NY. Never offered on the market until now. But with confidence - 20 years in the business. Vintage, Old, Original, Antique, NOT a Reproduction - Guaranteed!

O'Sullivan, known for his famous "Harvest of Death" photo, from the Battle at Gettysburg, and others. Photographer imprint at lower left - Negative by T. At lower right: Positive by A. At bottom edge, lower right - F. Dudley [Frederick Augustus Dudley - Madison Connecticut / King Ferry Cayuga County, New York], Surgeon in charge.

I believe this is the man standing in center of photo. The entire piece, including mount measures just under 8 x 10 inches. The actual albumen 8 3/8 x 6 3/8 inches. In good to very good condition.

Worn at edges; Albumen has a few small dings; a dew small chips to right side edge; surface wear to mount. Please see photos and feel free to ask questions. If you collect 19th century Americana history, photography, American photos, military, etc. This is a treasure you will not see again!

Add this to your image or paper / ephemera collection. Important genealogy research importance too. 1840 January 14, 1882 was a photographer widely known for his work related to the American Civil War and the Western United States. O'Sullivan's history and personal life remains a mystery for many historians as there is little information to work from.For example, he was either born in Ireland and came to New York City two years later with his parents or his parents traveled to New York before he was born. There is no way of finding out which of the two stories is true. We do know that as a teenager, he was employed by Mathew Brady. We also know when the Civil War began in early 1861, he was commissioned a first lieutenant in the Union Army (though Joel Snyder, O'Sullivan's biographer, could find no definitive proof of this claim in Army records).

There is no record of him fighting. [citation needed] Alexander Gardner worked as a photographer on the staff of General George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, and was given the honorary rank of captain. Gardner described O'Sullivan as the Superintendent of my map and field work.

Horan writes that O'Sullivan was a civilian photographer attached to the Topographical Engineers. His job was to copy maps and plans, but he also took photographs on his own time.

Although he later listed himself as a first lieutenant, the rank was likely honorary, like Gardner's. From November 1861 through April 1862, O'Sullivan, working for Gardner, followed Union forces to Fort Walker, Fort Beauregard, Beaufort, Hilton Head, [1] and Fort Pulaski. After being honorably discharged, he rejoined Brady's team. In July 1862, O'Sullivan followed Maj.John Pope's Northern Virginia Campaign. By joining Gardner's studio, he had his forty-four photographs published in the first Civil War photographs collection, Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War.

[2] In July 1863, he created his most famous photograph, "The Harvest of Death, " depicting dead soldiers from the Battle of Gettysburg. He took many other photographs documenting the battle, including "Dead Confederate sharpshooter at foot of Little Round Top", [3] "Field where General Reynolds fell", [4] "View in wheatfield opposite our extreme left", [5] "Confederate dead gathered for burial at the southwestern edge of the Rose woods", [6] "Bodies of Federal soldiers near the McPherson woods", [7] "Slaughter pen", [8] and others.Grant's trail, he photographed the Siege of Petersburg before briefly heading to North Carolina to document the siege of Fort Fisher. That brought him to the Appomattox Court House, the site of Robert E. Lee's surrender in April 1865.

From 1867 to 1869, he was the official photographer on the United States Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel under Clarence King. The expedition began at Virginia City, Nevada, where he photographed the mines, and worked eastward. In so doing, he became one of the pioneers in the field of geophotography. 1990 In contrast to the Asian and Eastern landscape fronts, the subject matter he focused on was a new concept.

It involved taking pictures of nature as an untamed, pre-industrialized land without the use of landscape painting conventions. O'Sullivan combined science and art, making exact records of extraordinary beauty.In 1870 he joined a survey team in Panama to survey for a canal across the isthmus. Wheeler in his survey west of the 100th meridian. His job was to photograph the West to attract settlers.

O'Sullivan's pictures were among the first to record the prehistoric ruins, Navajo weavers, and pueblo villages of the Southwest. [9] He faced starvation on the Colorado River when some of the expedition's boats capsized; few of the 300 negatives he took survived the trip back East. [citation needed] He spent the last years of his short life in Washington, D. As official photographer for the U.Geological Survey and the Treasury Department. O'Sullivan died in Staten Island of tuberculosis at age 42. Alexander Gardner (October 17, 1821 December 10, 1882) was a Scottish photographer who immigrated to the United States in 1856, where he began to work full-time in that profession. He is best known for his photographs of the American Civil War, U. President Abraham Lincoln, and the execution of the conspirators to Lincoln's assassination.

Alexander was born in Paisley, Renfrewshire, on 17 October 1821. He became an apprentice jeweller at the age of 14, lasting seven years. [3] Gardner had a Church of Scotland upbringing and was influenced by the work of Robert Owen, Welsh socialist and father of the cooperative movement. By adulthood he desired to create a cooperative in the United States that would incorporate socialist values. He stayed there until 1856, becoming owner and editor of the Glasgow Sentinel in 1851.Visiting The Great Exhibition in 1851 in Hyde Park, London, he saw the photography of American Mathew Brady, and thus began his interest in the subject. In 1856, Alex and his family immigrated to the United States. Finding that many friends and family members at the cooperative he had helped to form were dead or dying of tuberculosis, he stayed in New York. He initiated contact with Brady and came to work for him that year, continuing until 1862.

At first, Gardner specialized in making large photographic prints, called Imperial photographs, but as Bradys eyesight began to fail, Gardner took on increasing responsibilities. In 1858, Brady put him in charge of his Washington, D.Abraham Lincoln became the American President in the November 1860 election and along with his election came the threat of war. Gardner, being in Washington, was well-positioned for these events, and his popularity rose as a portrait photographer, capturing the visages of soldiers leaving for war.

Brady had the idea to photograph the Civil War. Gardner's relationship with Allan Pinkerton (who was head of an intelligence operation that would become the Secret Service) was the key to communicating Brady's ideas to Lincoln. Pinkerton recommended Gardner for the position of chief photographer under the jurisdiction of the U. Following that short appointment, Gardner became a staff photographer under General George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac.

At this point, Gardner's management of Brady's gallery ended. The honorary rank of captain was bestowed upon Gardner, and he photographed the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, developing photos in his travelling darkroom.

Gardner has often had his work misattributed to Brady, and despite his considerable output, historians have tended to give Gardner less than full recognition for his documentation of the Civil War. [6] Lincoln dismissed McClellan from command of the Army of the Potomac in November 1862, and Gardners role as chief army photographer diminished. About this time, Gardner ended his working relationship with Brady, probably in part because of Brady's practice of attributing his employees' work as "Photographed by Brady". [6] That winter, Gardner followed General Ambrose Burnside, photographing the Battle of Fredericksburg. Next, he followed General Joseph Hooker. In May 1863, Gardner and his brother James opened their own studio in Washington, D. C, hiring many of Brady's former staff. Gardner photographed the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1863) and the Siege of Petersburg (June 1864April 1865) during this time. Title page of Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War (1866), design by Alfred R. In 1866, Gardner published a two-volume work, Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the Civil War. Each volume contained 50 hand-mounted original prints.The book did not sell well. [7] Not all photographs were Gardner's; he credited the negative producer and the positive print printer. As the employer, Gardner owned the work produced, as with any modern-day studio. The sketchbook contained work by Timothy H.

Gibson, John Reekie, William Pywell, James Gardner (his brother), John Wood, George N. Barnard, David Knox and David Woodbury, among others.

Among his photographs of Abraham Lincoln were some considered to be the last taken of the President, four days before his assassination, although later this claim was found to be incorrect, while the pictures were actually taken in February 1865, the last one being on the 5th of February. [7][8] Gardner would photograph Lincoln on a total of seven occasions while Lincoln was alive.

[7] He also documented Lincoln's funeral, and photographed the conspirators involved (with John Wilkes Booth) in Lincoln's assassination. Gardner was the only photographer allowed at their execution by hanging, photographs of which would later be translated into woodcuts for publication in Harper's Weekly.

Portrait of Ta-Tan-Kah-Sa-Pah (Black Bull), 1872. After the war, Gardner was commissioned to photograph Native Americans who came to Washington to discuss treaties; and he surveyed the proposed route of the Kansas Pacific railroad to the Pacific Ocean. Many of his photos were stereoscopic. Gardner stayed in Washington until his death. When asked about his work, he said, It is designed to speak for itself. As mementos of the fearful struggle through which the country has just passed, it is confidently hoped that it will possess an enduring interest. [9] He became sick in the late fall of 1882 and died shortly afterward on December 10, 1882, at his home in Washington, D. He was survived by his wife and two children. [1] He was buried in local Glenwood Cemetery.Watson Porter, who had worked for Gardner years before, tracked down hundreds of glass negatives made by Gardner, that had been left in an old house in Washington where Gardner had lived. The result was a story in the Washington Post and renewed interest in Gardner's photographs. A Sharpshooter's Last sleep (1863).

The home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg (1863). , photographic analysis suggested that Gardner had manipulated the setting of at least one of his Civil War photos by moving a soldier's corpse and weapon into more dramatic positions. [12][13] In 1961, Frederic Ray of the Civil War Times magazine compared several of Gardner's Gettysburg photos showing "two" dead Confederate snipers and realized that the same body had been photographed in two separate locations.

One of his most famous images, "Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter", has been argued to be a fabrication. [citation needed] This argument, first put forth by William Frassanito in 1975[citation needed], goes this way: Gardner and his assistants Timothy O'Sullivan and James Gibson had dragged the sniper's body 40 yards into the more photogenic surroundings of the Devil's Den to create a better composition. Though Ray's analysis was that the same body was used in two photographs, Frassanito expanded on this analysis in his 1975 book Gettysburg: A Journey in Time, and acknowledged that the manipulation of photographic settings in the early years of photography was not frowned upon.There were five corps in the Union Army designated as II Corps (Second Army Corps) during the American Civil War. These formations were the Army of the Cumberland II Corps commanded by Thomas L.

Crittenden from October 24, 1862, to November 5, 1862, later renumbered XXI Corps; the Army of the Mississippi II corps led by William T. Sherman from January 4, 1863, to January 12, 1863, renumbered XV Corps; Army of the Ohio II Corps commanded by Thomas L.

Crittenden from September 29, 1862, to October 24, 1862, transferred to Army of the Cumberland; Army of Virginia II Corps led by Nathaniel P. Banks from June 26, 1862, to September 4, 1862, and Alpheus S. Williams from September 4, 1862, to September 12, 1862, renumbered XII Corps; and the Army of the Potomac II Corps from March 13, 1862, to June 28, 1865.Of these five, the one most widely known was the Army of the Potomac formation, the subject of this article. The II Corps was prominent by reason of its longer and continuous service, larger organization, hardest fighting, and greatest number of casualties. Within its ranks was the regiment that sustained the largest percentage of loss in any one action; the regiment that sustained the greatest numerical loss in any one action; and the regiment that sustained the greatest numerical loss during its term of service. Of the one hundred regiments in the Union Army that lost the most men in battle, thirty-five of them belonged to the II Corps.

The II Corps also fought in nearly every battle in the main Eastern Theater, from the 1862 Peninsula Campaign to the Confederate surrender at Appomattox Court House. The corps was organized under General Orders No. 101, March 21, 1862, which assigned Brigadier General Edwin Vose Sumner to its command, and Brigadier Generals Israel B. Richardson, John Sedgwick, and Louis Blenker to the command of its divisions.

Within three weeks of its organization the corps moved with George B. McClellan's Army of the Potomac on the Peninsula Campaign, except for Blenker's division, which was withdrawn on March 31 from McClellan's command, and ordered to reinforce John C. Frémont's army in western Virginia. Blenker's division never rejoined the corps. The remaining two divisions numbered 21,500 men, of whom 18,000 were present for duty. The first general engagement of the corps occurred at the Battle of Seven Pines, where Sumner's prompt and soldierly action brought the corps on the field in time to retrieve a serious disaster, and change a rout into a victory. In a fierce engagement with Confederate general Gustavus W. Gen Oliver Howard was shot in the arm and had to have it amputated, causing him to miss all of the summer campaigning of the army. The casualties of the two divisions in that battle amounted to 196 killed, 899 wounded, and 90 missing. In the Seven Days Battles, the II Corps was not engaged until Savage's Station when it held off Confederate general John B.The following day, the corps was engaged at Glendale, where John Sedgwick's division was in the thick of the fighting. Israel Richardson's division spent the battle to the north engaged in a standoff with "Stonewall" Jackson's troops on opposite sides of White Oak Swamp; fighting here was limited to artillery dueling. The corps was held in reserve at Malvern Hill. Total II Corps casualties in the Seven Days were 201 killed, 1,195 wounded, and 1,024 missing.

Afterwards, Sumner, Sedgwick, and Richardson all received promotions to major general as part of a blanket promotion of each corps and division commander in the Army of the Potomac. The II Corps spent the Northern Virginia Campaign in Washington D. And did not participate in it except at the very end when it moved out to cover the retreat of Maj. Gen John Pope's army. The corps then marched on the Maryland Campaign, during which time it received a new division of nine month troops headed by Brig.At the Battle of Antietam the corps was heavily engaged, its casualties amounting to more than twice that of any other corps on the field. Out of 15,000 effectives, it lost 883 killed, 3,859 wounded, and 396 missing; total, 5,138. Nearly one-half of these casualties occurred in Sedgwick's 2nd Division, in its bloody and ill-planned advance on the Dunker church, an affair that was under Sumner's personal direction; this included units like the 34th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment on the left flank of the division's 1st Brigade, as well as the 1st Minnesota Volunteer Infantry of later Gettysburg fame. The Irish Brigade, of Richardson's 1st Division, also sustained a terrible loss in its fight at the "Bloody Lane", but, at the same time, inflicted a greater one on the enemy.

This allowed Colonel Francis C. Barlow to lead the 61st and 64th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiments to break through the Confederate line. Sedgwick and Richardson were both wounded in the battle; the former eventually recovered and went on to corps command, the latter succumbed to an infection a month and a half after the battle. Oliver Howard succeeded to command of Sedgwick's division, Richardson's division was taken over by Brig.

Gen Winfield Hancock, brought over from the VI Corps as the ranking brigadier general in the division, John C. Caldwell, was too inexperienced and junior for the position. The next engagement was at the Battle of Fredericksburg. In the meantime Sumner had been promoted to the command of a Grand DivisionII and IX Corpsand General Darius N. Couch, a division commander of the IV Corps, was appointed to his place.

The loss of the corps at Fredericksburg exceeded that of any other in that battle, amounting to 412 killed, 3,214 wounded, and 488 missing, one-half of which fell on Hancock's Division in the unsuccessful assault on Marye's Heights. The percentage of loss in Hancock's division was high, Caldwell's brigade suffering 46% casualties.

After Fredericksburg, the Grand Divisions were discontinued and the aging Sumner decided to retire from command. Couch led the corps at the Battle of Chancellorsville, with Hancock, John Gibbon, and French as his division commanders. Sedgwick had been promoted to the command of the VI Corps, and Howard, who had commanded Sedgwick's Division at Fredericksburg, was promoted to the command of the XI Corps. At Chancellorsville, the principal part of the II Corps's fighting fell on Hancock's division, its skirmish line, under Colonel Nelson A.Miles, distinguishing itself by a successful resistance to a strong attack of the enemy, making one of the most interesting episodes in the history of that battle. During the fighting at Chancellorsville, Gibbon's 2nd Division remained at Fredericksburg, where it supported Sedgwick's operations, but with slight loss. Not long after Chancellorsville, Couch, unhappy with Joe Hooker's performance as army commander, resigned. Hancock assumed command of the corps, and Brigadier General John C. At the start of the Gettysburg Campaign, Brigadier General Alexander Hays' brigade joined, and was assigned to the 3rd Division, Hays taking command of the division.

At the Battle of Gettysburg, the corps was hotly engaged in the battles of the second and third days, encountering there the hardest fighting in its experience, and winning there its grandest laurels; on the second day, in the fighting at the Wheatfield, and on the third, in the repulse of Pickett's Charge, which was mostly directed against Hancock's position. The fighting was deadly in the extreme, the percentage of loss in the 1st Minnesota of Gibbon's Division, being almost without an equal in the records of modern warfare. The loss in the corps was 796 killed, 3,186 wounded, and 368 missing; a total of 4,350 out of less than 10,500 engaged.Gibbon's Division suffered the most, the percentage of loss in Brigadier General William Harrow's 1st Brigade being unusually severe. Hancock and Gibbon were seriously wounded, while of the brigade commanders, Samuel K.

Willard, and Eliakim Sherrill were killed. The monthly return of the corps, June 30, 1863, shows an aggregate of 22,336 borne on the rolls, but shows only 13,056 present for duty. From the latter deduct the usual proportion of non-combatantsthe musicians, teamsters, cooks, servants, and stragglersand it becomes doubtful if the corps had over 10,000 muskets in line at Gettysburg. Hancock's wounds necessitated an absence of several months. William Hays was placed in command of the corps immediately after the battle of Gettysburg, retaining the command until August 12, when he was relieved by Major General Gouverneur K. Warren had distinguished himself at Gettysburg by his quick comprehension of the critical situation at Little Round Top, and by the energetic promptness with which he remedied the difficulty. He had also made a brilliant reputation in the V Corps, and as the chief topographical officer of the Army of the Potomac. He was, subsequently, in command at the Battle of Bristoe Station, a II Corps affair, and one which was noticeable for the dash with which officers and men fought, together with the superior ability displayed by Warren himself. He also commanded at the Battle of Mine Run and Morton's Ford, the divisions at that time being under Generals Caldwell, Alexander S. Upon the reorganization of the Army of the Potomac, March 23, 1864, the III Corps was discontinued, and two of its three divisions were ordered transferred to the II Corps. Under this arrangement the II Corps was increased to 81 regiments of infantry and 10 batteries of light artillery. The units of the old II Corps were consolidated into two divisions, under Barlow (now a general) and Gibbon; the two divisions of the III Corps were transferred intact, and were numbered as the 3rd and 4th, with Generals David B.Birney and Gershom Mott in command. By this accession, the II Corps attained in April 1864, an aggregate strength of 46,363, with 28,854 present for duty. Hancock, having partially recovered from his wounds, resumed command, and led his battle-scarred divisions across the Rapidan River.

In the Battle of the Wilderness, the corps lost 699 killed, 3,877 wounded, and 516 missing; total, 5,092, half of this loss falling on Birney's 3rd Division. Alexander Hays, commanding the 2nd Brigade of Birney's Division, was among the killed.At the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House the II Corps again attained a glorious place in history by Hancock's brilliant and successful assault on the morning of May 12. During the fighting around Spotsylvania, Mott's 4th Division became so depleted by casualties, and by the loss of several regiments whose term of service had expired, that it was discontinued and merged into Birney's Division, Mott retaining the command of a brigade.

The casualties of the corps in the various actions around Spotsylvania, from May 8 to May 19, aggregated 894 killed, 4,947 wounded, and 801 missing; total 6,642, or over one-third of the loss in the entire Army of the Potomac, including the IX Corps. The heaviest loss occurred in Barlow's 1st Division.

Up to this time the II Corps had not lost a color nor a gun, although it had previously captured 44 stands of colors from the enemy. After more of hard and continuous fighting at the Battle of North Anna, and along the Totopotomoy, the corps reached the memorable field where the Battle of Cold Harbor was fought. While at Spotsylvania it had been reinforced by a brigade of heavy artillery regiments, acting as infantry, and by the brigade known as the Corcoran Legion, so that at Cold Harbor it numbered 53,831, present and absent, with 26,900 "present for duty". Its loss at Cold Harbor including eleven days in the trenches, was 494 killed, 2,442 wounded, and 574 missing; total, 3,510.

Birney's Division was but slightly engaged. In the assaults on the Petersburg entrenchments, June 16 June 18, the Corps is again credited with the largest casualty list. In one of these attacks, the 1st Maine Heavy Artillery sustained the greatest loss of any regimental organization in any one action during the war. At this time the corps contained 85 regiments; its effective strength, however, was less than at a previous date. By late June 1864, the II Corps's effectiveness as a fighting force had been severely diminished by almost two months of continuous fighting.

Of the approximately 30,000 men in the corps at the start of the Overland Campaign, 20,000 of them had been lost since then, for a 68% casualty rate. Over half the brigade commanders the corps had had in April had been killed or wounded since then, and over 100 regimental commanders. With most of the best officers and men gone, the II Corps went from being the Army of the Potomac's elite shock troops to the smallest and weakest corps in the army.

On June 2123, the II Corps engaged in the Battle of Jerusalem Plank Road where it tried to extend the army's left flank. Hill's Confederate troops moved down to oppose them, and the II Corps was repulsed.

Actual battlefield casualties were light, however 1,700 men were taken prisoner by the Confederates, including several whole regiments, some of them, such as 15th Massachusetts, once elite outfits. At the Battle of Boydton Plank Road, October 27, 1864, the division commanders were Generals Thomas W. Egan and Mott, the 1st Division Nelson A. Miles's, being retained in the trenches. In November, 1864, Hancock was assigned to other duty, and Major General Andrew A. Humphreys, chief of staff to the Army of the Potomac, succeeded to his position. Humphreys was in command during the final campaign, the divisions being under Generals Miles, William Hays, and Mott. The corps fought its last battle at Farmville on April 7, 1865, two days before Lee's surrender. In this final action Brigadier General Thomas A. Smyth of Hays' 2nd Division, was killed. Smyth was an officer with a brilliant reputation, and at one time commanded the famous Irish Brigade. Recent scholarship notes the quality not just of II Corps' leadership but its individual soldiers, addressing both individual bravery and deep commitment to the Union as depicted in letters and diaries. In spite of homesickness and coming from Democratic homes and ethnic communities which did not favor expanding war aims to emancipation, soldiers of II Corps saw the fighting through, re-enlisting in 1863-4 and voting overwhelmingly for Abraham Lincoln in 1864.Pride in unit featured prominently in post-war reunions, and on the 50th anniversary of Gettysburg Speaker of the House Champ Clark from Missouri referred to soldiers of II Corps as "those unconquerable boys in blue". Unit cohesion ultimately overcame racial antipathies, frustrations and hatreds according to this analysis. March 13, 1862 October 7, 1862.

October 7, 1862 December 26, 1862. December 26, 1862 January 26, 1863. January 26, 1863 February 5, 1863.

February 5, 1863 May 22, 1863. May 22, 1863 July 1, 1863. July 1, 1863 July 2, 1863. July 2, 1863 July 3, 1863.

July 3, 1863 August 16, 1863. August 16, 1863 August 26, 1863. August 26, 1863 September 2, 1863.

September 2, 1863 October 10, 1863. October 10, 1863 October 12, 1863. October 12, 1863 December 16, 1863. December 16, 1863 December 29, 1863. December 29, 1863 January 9, 1864. January 9, 1864 January 15, 1864. January 15, 1864 March 24, 1864. March 24, 1864 June 18, 1864. June 18, 1864 June 27, 1864. June 27, 1864 November 26, 1864. November 26, 1864 February 15, 1865. February 15, 1865 February 17, 1865. February 17, 1865 February 25, 1865.February 25, 1865 April 22, 1865. April 22, 1865 May 5, 1865. May 5, 1865 June 9, 1865. June 9, 1865 June 20, 1865. June 20, 1865 June 28, 1865.

Brandy Station is an unincorporated community in Culpeper County, Virginia, United States. [1] Its original name was Brandy. The name Brandy Station comes from a local tavern sign that advertised brandy. Brandy Station was the site of the 1863 Battle of Brandy Station, the largest predominantly cavalry engagement of the American Civil War as well as the largest to take place ever on American soil. Auburn, Farley, and the Graffiti House are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Culpeper Regional Airport is located on Beverly Ford Road in Brandy Station. The American Civil War (also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States from 1861 to 1865, fought between the northern United States (loyal to the Union) and the southern United States (that had seceded from the Union and formed the Confederacy). [e] The civil war began primarily as a result of the long-standing controversy over the enslavement of black people. War broke out in April 1861 when secessionist forces attacked Fort Sumter in South Carolina shortly after Abraham Lincoln had been inaugurated as the President of the United States.The loyalists of the Union in the North, which also included some geographically western and southern states, proclaimed support for the Constitution. They faced secessionists of the Confederate States in the South, who advocated for states' rights in order to uphold slavery. States in February 1861, seven Southern slave states were declared by partisans to have seceded from the country, and the so-called Confederate States of America was organized in rebellion against the U. The Confederacy grew to control at least a majority of territory in eleven states, and it claimed the additional states of Kentucky and Missouri by assertions from native secessionists fleeing Union authority. These states were given full representation in the Confederate Congress throughout the Civil War.

The two remaining "slave" states, Delaware and Maryland, were invited to join the Confederacy, but nothing substantial developed due to intervention by federal troops. The Confederate states were never diplomatically recognized as a joint entity by the government of the United States, nor by that of any foreign country. [f] The states that remained loyal to the U. Were known as the Union. [g] The Union and the Confederacy quickly raised volunteer and conscription armies that fought mostly in the South over the course of four years.

Intense combat left 620,000 to 750,000 people dead, more than the number of U. Military deaths in all other wars combined.The war effectively ended April 9, 1865, when General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at the Battle of Appomattox Court House. Confederate generals throughout the southern states followed suit, the last surrender on land occurring June 23. Much of the South's infrastructure was destroyed, especially the transportation systems.

The Confederacy collapsed, slavery was abolished, and four million black slaves were freed. During the Reconstruction era that followed the war, national unity was slowly restored, the national government expanded its power, and civil and political rights were granted to freed black slaves through amendments to the Constitution and federal legislation. The war is one of the most studied and written about episodes in U. The item "RARE Orig Albumen Photo Timothy H O'Sullivan 1864 Civil War Hospital Gardner" is in sale since Wednesday, January 1, 2020. This item is in the category "Collectibles\Militaria\Civil War (1861-65)\Original Period Items\Photographs". The seller is "dalebooks" and is located in Rochester, New York. This item can be shipped worldwide.- Modified Item: No

- Country/Region of Manufacture: United States